Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Recently, the state of Oregon has used copyright law to threaten people who were publishing its laws online. Can they really do that? More to the point, why would they? This essay will put the Oregon fracas in historical context, and explain the public policies at stake. Ultimately, it’ll try to convince you that Oregon’s demands, while wrong, aren’t unprecedented. People have been claiming copyright in “the law” for a long time, and at times they’ve been able to make a halfway convincing case for it. While there are good answers to these arguments, they’re not always the first ones that come to hand. It’s really only the arrival of the Internet that genuinely puts the long-standing goal of free and unencumbered access to the law within our grasp.

A few disclaimers:

“The law” comes in many forms. Lawyers commonly talk about three major kinds, which correspond to the three branches of government:

This list is massively incomplete, but it should provide an idea of the range of things that government does that create law. Statutes, regulations, and opinions are the big three: These are the ones that a lawyer who needs to know what the law is on a given point will typically consult first. I've used the federal government as an example, but states, counties, cities, and other units of government are also in the lawmaking game and produce their own legal materials.

Let’s start with an example of what access to the law looks like today.

In one corner, Justia.com is one of many online legal publishers. It has a large database of state and federal law, which it makes freely available on its website. There, you can look up case law from various courts, search for dockets of pending cases, and sometimes even see the documents parties have filed. You can also browse and search statutes and regulations, download legal forms, and soon.

To repeat, Justia is free to use. Its business model–in a classic Web 2.0 play–is to draw in users using the free legal materials as a complement to their real moneymaker: helping lawyers market themselves. (Even if you don’t think people who come for the law will stay for the lawyers, the clean design of Justia’s free legal resources is certainly a good advertisement for its ability to design good web sites for law firms.)

So this is an example of using technology to enhance access to the law. By using Internet technologies, Justia makes it more convenient for the public to find out what the law says. The cases and statutes and such it provides are matters of public record, and are available in governmental reading rooms, libraries, and websites. Justia just makes them easier to find and to consult.

In the other corner, we have the State of Oregon. As one might expect, Oregon has laws. Oregon puts them online; so does Justia. Both Oregon’s and Justia’s versions of the Oregon Revised Statutes are freely available, sorted by title and chapter number, with some formatting to make the structure clearer.

In early April of 2008, Oregon sent Justia a cease-and-desist letter telling them to cut it out. According to Oregon, Justia could either enter into a licensing agreement (and pay Oregon for the privilege) or remove the Oregon Revised Statutes from its site. This may seem a rather strange thing for a government to be doing: telling people to make it harder for the public to find out what the law says. It only get stranger as you dig deeper. Oregon tells its Office of Legislative Counsel to publish both print and online versions of its statutes. And the OLCC has a little something to say about copyright. This is the start of the copyright notice they attach to the web version:

The Oregon Revised Statutes and all specialty publications produced by the Office of the Legislative Counsel are copyrighted by the State of Oregon and may not be reproduced or distributed by any means or in any manner without the written permission of the Office of the Legislative Counsel.

This claim is even more remarkable. Not only the state of Oregon, but the very people whose official mission it is to maximize public access to the law are in fact the ones sending out the cease-and-desist letter telling other people to stop making the law accessible. So this ultimately an issue of access to the law as abetted by technology and perhaps as hindered by copyright or perhaps as facilitated by it.

And here’s the thing: We’ve been here before. Providing the public with access to the law is not a new problem; this confluence of copyright, technology, and access is not a new phenomenon.

“But the plans were on display…”

“On display? I eventually had to go down to the cellar to find them.”

“That’s the display department.”

“With a flashlight.”

“Ah, well, the lights had probably gone.”

“So had the stairs.”

“But look, you found the notice, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” said Arthur, “yes I did. It was on display on the bottom of a locked filing cabinet stuck in a disused lavatory with a sign on the door saying ‘Beware of the Leopard.’”

–Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Why do we care so much about access to the law? I think we can agree that it’s clearly wrong to make the documents that constitute the law accessible only by putting them on display on the bottom of a locked file cabinet stuck in a misused lavoratory with a sign on the door saying “Beware of the Leopard.” But why? What’s wrong with this approach to government? At least four things:

Democracy: Rule by secret law is perhaps indistinguishable from rule by no law whatsoever. It’s fundamental to democracy and the rule of law that rules be announced and applied all prospectively. A government that only uses secret laws can rule with impunity; it can change the laws on the on the fly; it can simply act and make up the laws in hindsight so that whatever it does turns out to be allowed. Thus, requiring laws to be published acts as a restraint on the exercise of arbitrary government power. It’s the first measure of transparency and accountability, the one on which every subsequent measure depends.

Fairness: Even in a functioning democracy, deficient access to law is dangerous. The rule of law only works if people actually know the laws. There are legal maxims that express this idea, such as “Everyone is presumed to know the law” and “Ignorance of the law is no defense.” These maxims are only fair–they are only reasonable principles rather than cruel jokes–if the public in fact has an opportunity to learn the content of the law. It’s ridiculous, both morally and pragmatically, to expect someone to comply with a set of rules that he has no reasonable chance of learning. It’s literally Kafkaesque, and incidentally violates the Due Process Clause of the constitution.

Consistency: Access to the law is also vital to the idea of law as a system of rules. You can’t act consistently if you have no memory of what happened last time. While either of two rules might be fair if applied consistently, oscillating back and forth between then is pure chaos. There’s a rule in administrative law that agencies aren’t free to reverse their own prior decisions without providing some reason for the switch. This is the rule of stare decisis in the courts and it obviously depends on having some accurate information about what happened in previous cases.

Equality: Unequal access to the law creates substantive inequality. If law is only available to those who have the resources to go and seek it out–a well paid lawyer, a better library, access to expensive services like Westlaw and Lexis–then people who can afford better access can afford better outcomes. This means that the rich can take advantage of law in ways that the poor can’t. Worse, it means that they can set traps to ensnare their less legally educated opponents. Law law becomes the servant of those with better access to it; it takes their side, exacerbating inequality.

None of these things are new problems.

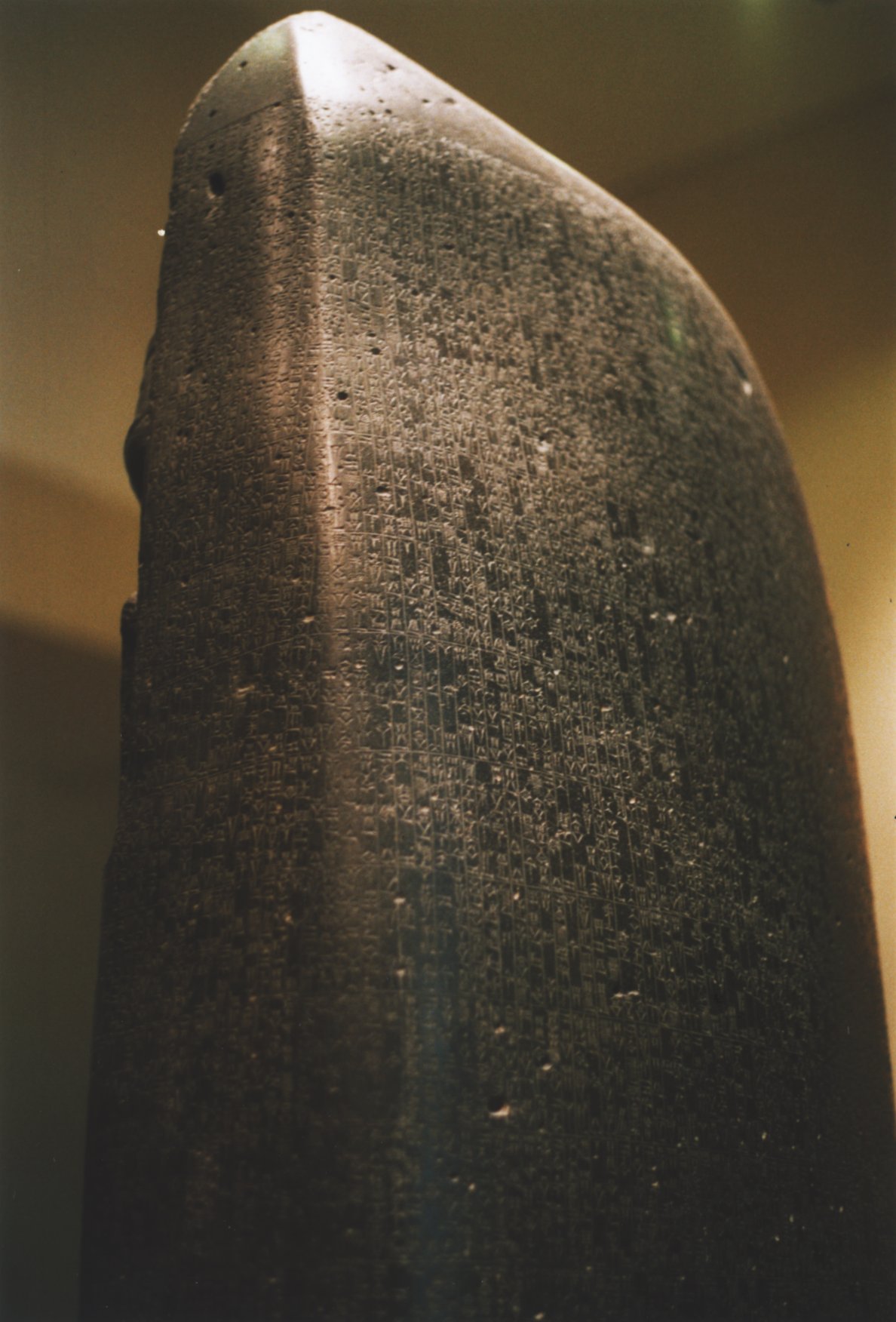

Consider this rock: the Code of Hammurabi. It’s a bit under four millennia old and even there, you can see some very modern things. While this is a highly visible artifact–8 feet tall and carved out of solid black basalt–literacy in Babylonian society was low. Only members of the priestly caste and a few others were able to read this and even a skilled reader would have a difficult time reading the 282 laws inscribed on the surface. That doesn’t, however, stop the code from declaring in its epilogue that “Hammurabi did teach the land these laws.” Even at this early stage, the Babylonian legal system was taking the problem of notice seriously.

Note also a few other features of this piece of legal access technology:

Fast-forward a few millennia, and legal publication is still grappling with these same issues. Here are a few snapshots from England’s long and halting progress towards widespread access to the law. If there’s a recurring theme, it’s that good legal publishing is hard.

Within 150 years after the Norman Conquest, England’s royal courts started keeping parchment plea rolls to track the results of cases. They reported the nature of the lawsuit and who won, but in formulaic terms that provided no factual details or legal explanation. They were thus completely inadequate at meeting the needs of actual lawyers and their clients–who need to know which arguments will win in court and which will lose.

Instead, by 1300 or so, lawyers were consulting anonymous and often sketchy outlines of the arguments made in court, compiled in volumes called the year books. While they became standard sources for lawyers and judges to consult in looking up the law, over the years their disorganization became a serious problem. It’s a painful task to have to search through centuries of handwritten volumes without an index, especially when you’re looking for rough analogies rather than exact matches.

The Abridgments

One way the legal profession responded to the disorganization of the year books was to produce abridgments: volumes of abbreviated case reports, arranged by topic. The abridgments employed organizational techniques that included alphabetical arrangement by topic, hierarchical indices, and notes in the margin to aid quick browsing. While some editors produced abridgments by hand, they really only became competitive around 1500, with the availability of the printing press. It’s hard to produce and maintain all that organizational material without the technological assistance of movable type.

For all their virtues, the abridgments had their own issues. Despite the great labor involved in producing an abridgment of ten or twenty thousand cases, or perhaps because of it, their editorial quality was often poor. Here’s a passage from (U.S. Supreme Court Justice) Joseph Story’s review of Charles Viner’s 24-volume 18th-century abridgement:

It is a cumbrous compilation, by no means accurate or complete in its citations, and difficult to use, from the irregularity with which the matter is distributed, and from the inadequacy, and sometimes the inaptness of the subdivisions. Indeed everything appears to have been thrown into it, without any successful attempt at method or exactness.

Eventually, the anonymous yearbooks were displaced by nominative (or “named”) reports, i.e. volumes of cases produced by specific editors who named their reports after themselves. This is a familiar shift in copyright history; going from script to print means both that the author becomes more important and that charging for copies becomes the dominant business model. By modern standards, the early nominative reports were woefully incomplete. In 1571, Edmund Plowden produced two carefully-edited volumes, but they covered a grand total of 62 cases. The second attempt was an 1582 collection of notes by Sir James Dyer (who had died in 1579), which mixed reports of actual cases with reports of dinner conversations. Sir Edward Coke, another judge, reported many cases starting in 1606, but sometimes falsified precedents, when doing so would support his position in a case. After Coke, no one tried again until the 1640s. Meanwhile, the yearbooks had petered out in the 1530s, which leaves quite a gap.

Over the years, there were more and more of these nominative reports. Some were excellent; many were terrible. An 1849 report on the system noted the inconsistencies among various competing reporters, the resulting inaccuracies and gaps, and the enormous cost to lawyers who needed to buy copies of multiple reporters’ sets in order to have everything relevant. It concluded:

To sum up in a few words the evils and inconveniences of the existing system of Law Reporting, there is no guarantee afforded to the public that the judicial exposition of the law will be reported at all, or reported correctly–or in time to prevent mistakes–or in such a manner, with respect to conciseness, form, and price, as to be accessible to those whom it so vastly affects.

The Law Reports produced by the independent, unpaid committee ultimately set up in response to the report became the English standard. And yet the profession hated them for many decades: they were slow, badly indexed, badly arranged, and–astonishingly enough–printed some cases repeatedly and other, important ones not at all. Nonprofit, quasi-public reporting turned out to have most of the same defects as private control over case law had.

Another instructive example involves not case law, but legislation. Consider the Statutes of the Realm, the first official attempt to provide a comprehensive collection of the legislation passed by Parliament in all of English history. It appeared in nine volumes and took twelve years to compile. The result of this extensive effort, completed in 1822, was to produce a relatively complete set of laws all the way up through . . . 1714. The Statutes of the Realm were over a century out of date on the day they first came off the printing presses! Perhaps unsurprisingly, practicing English lawyers turned instead to a privately-produced set, Chitty’s Statutes of Practical Utility. This is an important point, and it bears repeating: From the perspective of the people who most regularly needed to consult these legal materials, a private editor did a better job than the men with the official governmental commission to make the laws widely available.

Enough ancient history. Let’s cross the Atlantic and continue our story by looking at the roots of modern American copyright doctrine on legal materials.

Legal publication in the U.S. didn’t get off to a good start. In its early years, the U.S. Supreme Court didn’t produce printed opinions. Even today, we don’t have copies of all Supreme Court cases. The first published reports of Supreme Court cases come from Alexander Dallas, who was actually reporting Pennsylvania cases and decided to report the U.S. Supreme Court because it was sitting at the time in Philadelphia. His first volume, published in 1798, contained a grand total of five cases from the Supreme Court–decided between 1791 and 1793. As for his accuracy, the best that we can say is that we have nothing to compare it against, since we don’t have the originals. This sad state of affairs continued through the term of Dallas and his successor, William Cranch, . . .

. . . until this man, Henry Wheaton, entered the picture in 1816. If this story has a hero, it’s Henry Wheaton. If it has a villain, it’s also Henry Wheaton. His 11-year tenure as Supreme Court reporter was marked by a number of innovations, some of which may sound interestingly familiar.

In 1829, Wheaton’s successor, Richard Peters, brought out inexpensive, smaller versions of cases first reported by his predecessors. He omitted the marginal notes and deleted the scholarly essays, but he took the text of Wheaton’s cases word for word. Wheaton sued. The resulting case, Wheaton v. Peters, decided by the Supreme Court in 1834, is famous in American law as the first Supreme Court case on copyright. (Among other things, it’s the source of the statement that United States copyright is exclusively statutory. Copyright covers only those things that Congress wishes it to cover.) Right at the end, almost as an afterthought, the Court says:

It may be proper to remark that the Court is unanimously of opinion that no reporter has or can have any copyright in the written opinions delivered by this Court, and that the judges thereof cannot confer on any reporter any such right.

So this is the initial statement of rule that the law is not a proper subject for copyright. Wheaton tried to get a copyright by intermingling his additions with the public domain texts underneath. Peters got around Wheaton’s trick by extracting the underlying material, reprinting only the stuff that came from the court. So Wheaton v. Peters, in effect, says that Wheaton’s intermingling doesn’t take the underlying kosher public domain materials and render them treyf. Peters was free to publish his cheaper editions.

But think about the incentives that this decision gives to potential reporters. Until Henry Wheaton’s innovations, Supreme Court reporting had been a money-losing business. No one had been able to make it work. Dallas’s and Cranch’s reports were too slow and too inaccurate to meet lawyers’ needs. Wheaton did the job right. But doing the job right proved to be nearly impossible without copyright’s incentives. While Peters nominally won, the decision left him and his successors with no clear way to assert copyright in their work. For the next several decades, the general consensus was that the Supreme Court reports were no good.

Shepard’s

Another important landmark in legal publishing technology from the late 19th century was Shepard’s Citations. To appreciate its importance, it helps to understand the problem it solves.

Lawyers are always looking for legal “authorities” (e.g. cases, statutes, regulations, and so on) that support their positions. For an authority to be useful, it needs both to say something relevant and to be “good law,” that is, not to have been rendered obsolete by later developments. New statutes replace old ones, higher courts overrule lower ones, and so on. This evolutionary process means that even a lawyer holding in her hands a legal document that would perfectly, completely resolve her question isn’t out of the woods. Even if it’s only a week old, something might have happened since then to transform it from a gold-plated authority into worthless scrap paper.

In one direction, the problem is comparatively easy. If a court is overruling its earlier decision in Joe v. Blow, its opinion will typically contain a sentence such as, “Therefore, we now choose to overturn the rule of Joe v. Blow, 23 Foo.2d 400.” The reader of this passage knows that it affects Joe v. Blow; the court is kind enough to name it and cite it. The hard part is going in the opposite direction. Starting from Joe v. Blow, how do you know which later cases cite it? It’s not as though the Joe v. Blow court can look into the future, see that ten years hence State v. Hutz will come along, and insert a citation to it.

In 1875, Frank S. Shepard started constructing a reverse index. As each new case came along, he’d make notes of which cases it cited. As long as he caught every new case, he could be sure that he’d catch every case citing Joe v. Blow. His company sold the reverse index to lawyers, first as stickers (to paste into the lawyer’s copy of a case report) and then as actual printed volumes. The lawyer looking up Joe v. Blow in one of Shepard’s “citators” would see a list of citations, each of them referring to a later case citing Joe v. Blow. Other cases might still call it into question indirectly, but a lawyer using a good citator can be confident that she’s looked at every later case that explicitly refers to the case she cares about. This kind of exhaustive search is a regular part of careful legal research; it’s a way of avoiding nasty surprises.

For our purposes, three things are worth noting about Shepard’s:

Let’s jump ahead to the story of how later reporters in the 19th century figured out how to do, more or less, what Wheaton hadn’t. Starting in 1876, John B. West produced a series of reporters tied to geographic regions. Each reporter covered several states’ worth of courts (including the federal courts in those states). By 1887, he had expanded to national coverage, very much on Wheaton’s model; careful editing, lots of additional material, and strong copyright claims. His production process was a good example of late 19th-century information workflow. Very carefully structured, it took the handwritten decisions as they came from the judges and passed them through a group of clerks who not only typeset the opinions but also proofread them and arranged them. The process took advantage of substantial economies of scale in printing and in managing the clerical work.

To this, West added a system of key numbers, essentially a hierarchical taxonomy of legal topics, the idea being that any legal question whatsoever could be classified using some number. For example, 99 is “Copyrights and Intellectual Property,” 99.I is “Copyrights,” 99.I(A) is “Nature and Subject Matter,” and 99.I(A)k14 (which can be abbreviated to 99k14) is “Statutes and Law Reports,” the key number that covers essentially this entire essay. If you look under that number in one of West’s printed indexes (or on Westlaw, its online service), you’ll find Wheaton v. Peters and other cases dealing with these issues of copyright in the law.

This is a fairly typical page from a modern reporter in the West system. Let’s pull it apart into its constituent elements, to see how the copyright claim fits together.

The tradition hereabouts is that one cites a case by listing the name of the reporter in which the version cited appears, the volume number within that series, and the number of the page on which the case starts. Thus State v. Commemorative Services Corporation, the case we’re looking at here on the right-hand-page, would be as “823 P.2d 831.” That’s volume 823 of the second series of the Pacific Reporter (abbreviated to P.2d) at page 831.

While technically, a lawyer could cite to any reporter in which the case appears, there are enormous network effects at work. If you produce a reporter that’s more commonly used than other reporters, as West’s reporters were by the early twentieth century, then courts come to expect citations to those reporters. Lawyers stock the dominant reporter in their libraries; the value of providing citations to any other reporter drops. Ultimately, the citation system becomes the hook that makes West’s reporters the ones every lawyer has to buy. Today, there are about 20 states where the West reporter is the only available source for published court decisions.

This standardization on West page numbers gives West ammunition to argue that it has a copyright not merely in its editorial additions, but also its arrangement of cases within the volumes. More precisely, the page numbers become artifacts of the order of cases in a volume, and the editorial decisions West makes in choosing how to order them (for example, here West is grouping two cases from Kansas) become the basis of a claim to copyright.

West is hardly the only one trying something like this. Plenty of other entities are claiming that their annotations of the law or citations to the law are copyrighted:

West has gone computerized, and so has its arch-rival, LexisNexis. Both of them have extensive online databases of primary and secondary legal materials. These databases–which one used to access via direct dial-up–are now on the Web, wrapped in dire copyright warnings and extensive terms of service.

The American Medical Association produces a standardized taxonomy of medical billing codes. The taxonomy is privately drafted, but the federal government requires that Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement paperwork use its codes. The AMA claims that its taxonomy is copyrightable. A federal appeals court agreed. as did one considering a similar code produced by the American Dental Association.

Similarly, cities require that all new buildings be constructed to standards specified in building codes. The private construction industry trade associations that draft the building codes assert copyright over them. In a closely contested 8-6 decision, a federal appeals court threaded the needle: It’s legal to make copies of a town’s law, but not of a building code as such. Thus, what would otherwise be an infringing copy of a building code becomes legal if it’s made as a copy of “the law.”

How about tax maps? New York City makes maps of property lines to determine the assessment boundaries for property taxes. It’s gone to court to assert its copyright in those maps–and won. (That case isn’t publicly accessible online, oh the irony, but here’s an earlier one on the same issues.)

Out in Wisconsin, a private company has even attempted to use copyright to limit the use of tax assessment data. Not data that it created, not data that it gathered, but just data that city employees used its software to gather. The court that heard this case rejected this argument, saying, “It would be appalling if such an attempt could succeed.”

The lay reader may be forgiven for wondering whether lawyers have lost their minds, that such claims are not immediately laughed out of court. So let’s talk briefly about why these things are not obviously forbidden under copyright law.

The first line of defense is 17 U.S.C. § 105:

Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government, but the United States Government is not precluded from receiving and holding copyrights transferred to it by assignment, bequest, or otherwise.

If the United States government writes it, it’s not copyrightable. This is in one sense a natural consequence of the rule from Wheaton v. Peters. But the rule is both broader and narrower than we’d like if we’re thinking about access to the law. It’s broader in that there are lots of other federal works that are not copyrightable. For example, NASA’s space photographs aren’t copyrighted and they’re freely usable by anyone. But the rule is limited to the federal government. Congress hasn’t prohibited states or cities from taking copyright in the works they produce.

Another common approach is to emphasize 17 U.S.C. § 103, which deals with “compilation” copyrights. If you gather together a bunch of uncopyrightable things, the things themselves don’t suddenly become copyrightable merely because you collected them. If you take a group of public domain poems, such as Shakespeare’s sonnets, you can’t recopyright them. This is an important principle, but it’s also limited. The rule that compilation copyrights don’t cover underlying material is part of a larger provision that says that copyright is available for the compilation as a whole. If I took Shakespeare’s sonnets and arranged them into an original order that I thought displayed the logical progression of the author’s emotional relationship with the Dark Lady that might well be copyrightable as an original arrangement. The same would be true if I wrote an introductory essay, or short summaries of each sonnet. Add additional material, and you get a copyright in that additional material.

The result is that these modern Wheatons engage in a process of intermingling. They take public-domain legal material, add some copyrightable bells and whistles, and make their combined version the easiest, most accessible form of the law. If it should so happen that their copyrightable contributions are now hard to separate from the underlying public-domain matter, well, that’s just too bad for the rest of us.

Let’s pull up Oregon’s copyright notice again:

The Oregon Revised Statutes and all specialty publications produced by the Office of the Legislative Counsel are copyrighted by the State of Oregon and may not be reproduced or distributed by any means or in any manner without the written permission of the Office of the Legislative Counsel. This copyright extends solely to the organizational scheme of the statutes, the numbers and leadlines that appear at the head of each section, all notes and prefatory material, the index, the annotations, all tables and any other material produced by the Office of the Legislative Counsel as part of the compilation and production of the Oregon Revised Statutes or any specialty publication. The State of Oregon disclaims any copyright in the text of the statutes as enacted by the Oregon Legislative Assembly. Any person may refer or cite to any portion of the Oregon Revised Statutes in any work, including to any section number, and may quote from any copyrighted portion of the Oregon Revised Statutes to the extent consistent with fair use under Title 17 of the United States Code

That’s a bit complicated, so let’s see how the State of Oregon would apply this policy to its statutes. (We’ll return to the highlighted passage in a moment.) We’ll start with a bit of text from Oregon’s own web site:

JURISDICTION AND VENUE

14.030 Jurisdiction as affected by place where cause of action or suit arises. When the court has jurisdiction of the parties, it may exercise it in respect to any cause of action or suit wherever arising, except for the specific recovery of real property situated without this state, or for an injury thereto.

14.035 [1963 c.352 §1; 1975 c.628 §2; 1979 c.246 §2; repealed by 1979 c.246 §7]

There’s a bit of actual statutory text in the middle, a piece of law enacted by the legislature. In the third sentence of its copyright notice, Oregon concedes that yes, Wheaton v. Peters requires that this part be public domain. (How generous.) So let’s color that part green (for “go ahead and copy”):

JURISDICTION AND VENUE

14.030 Jurisdiction as affected by place where cause of action or suit arises. When the court has jurisdiction of the parties, it may exercise it in respect to any cause of action or suit wherever arising, except for the specific recovery of real property situated without this state, or for an injury thereto.,

14.035 [1963 c.352 §1; 1975 c.628 §2; 1979 c.246 §2; repealed by 1979 c.246 §7]

But now, let’s look back at the second sentence of the copyright notice, the one highlighted in the long quotation above. Yes, Oregon uses the word “solely,” but this is really a long list of things over which it does claim copyright. We can start by coloring the “numbers and leadlines that appear at the head of each section” in red (for “stop, you infringer!”):

JURISDICTION AND VENUE

14.030 Jurisdiction as affected by place where cause of action or suit arises. When the court has jurisdiction of the parties, it may exercise it in respect to any cause of action or suit wherever arising, except for the specific recovery of real property situated without this state, or for an injury thereto.

14.035 [1963 c.352 §1; 1975 c.628 §2; 1979 c.246 §2; repealed by 1979 c.246 §7]

Now, let’s add the “organizational scheme of the statutes”:

JURISDICTION AND VENUE

14.030 Jurisdiction as affected by place where cause of action or suit arises. When the court has jurisdiction of the parties, it may exercise it in respect to any cause of action or suit wherever arising, except for the specific recovery of real property situated without this state, or for an injury thereto.

14.035 [1963 c.352 §1; 1975 c.628 §2; 1979 c.246 §2; repealed by 1979 c.246 §7]

And now, let’s fill in the “notes and . . . annotations.” The second section here has a historical note. Color it red! (Yes, historical facts are not copyrightable. If push came to shove, Oregon would probably argue that it’s chosen an original way of presenting those facts. That argument would fail, because they arrangement it chose–basically chronological–is so trivial. But one could imagine more complicated annotations that would pass copyright’s low threshold of sufficient originality.)

JURISDICTION AND VENUE

14.030 Jurisdiction as affected by place where cause of action or suit arises. When the court has jurisdiction of the parties, it may exercise it in respect to any cause of action or suit wherever arising, except for the specific recovery of real property situated without this state, or for an injury thereto.

14.035 [1963 c.352 §1; 1975 c.628 §2; 1979 c.246 §2; repealed by 1979 c.246 §7]

That’s an awful lot of red–and it includes the section numbers, which are the key to the citation system for the Oregon Revised Statutes (the same way that West’s pagination is the key to its case citation system). If you accept this theory of copyright–as some courts have done–what Justia did would constitute open-and-shut infringement.

It’s worth emphasizing an important distinction between the green stuff and the red stuff. The green stuff—the statutory text—is passed as a bill by the Oregon legislature and signed into law by the governor. The red stuff—including especially the section numbers—is written by state bureaucrats after the bill becomes a law. (Learn more than you ever wanted to know about legislative drafting in Oregon here.) Oregonians are expected to comply with the rules set forth in the green parts; those are the law of Oregon. No one is expected to obey the number “14.030.” It’s just an annotation that makes it easier to look up the actual law. The numbers are written by a governmental body, but they’re not actually law.

Codification—the process of pulling together a body of law into one convenient place—is one of the classic hard problems of access to the law. It never seems hard when one sets out; back in Merrie Olde 12th century England, Parliament’s practice was to take new laws, copy out a handful of copies by hand, circulate those copies to various local officials, and call it a day. The problem that Statutes of the Realm was trying to deal with was that seven centuries later, this sequential process had produced such a vast body of accumulated laws that merely compiling the index took four years.

In the 1930s in the U.S., the alphabet soup of newly created New Deal agencies produced a similar mess. One infamous 1935 case, Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan (colloquially known as the “Hot Oil case,” because it dealt with illegal interstate shipments of petroleum), reached the Supreme Court before anyone realized that one of the laws the government was trying to enforce against the oil companies wasn’t in force at the relevant time. It had been repealed (by mistake, it turned out) over a year before, without anyone noticing. People had been threatened with criminal punishment for violating a “law” that wasn’t. The outcry—at least among law professors—led to the establishment of the Federal Register, a chronological log of all the regulatory actions taken by federal agencies, and the Code of Federal Regulations, which captures a current snapshot of the regulations currently in force.

There are various codification strategies out there, with advantages and drawbacks that would take us too far afield to discuss in much detail. One strategy is for someone with a lot of time to pore through the last N years of statutes, pull out the ones that are still relevant, and compile them into a single, authoritative text. The legislature then repasses the authoritative version, and repeals everything else. Another is for someone simply to compile the reams and reams of statutes into a logical arrangement that then becomes evidence of what the law says; if you really want to get it right, you need to go back and check the original act as it was passed. Governments in the U.S. use a mixture of both of these processes. Once you have a compilation of this sort, it becomes much easier for the legislature to make changes in place. They can say “we’re repealing this section and replacing it with this new text,” which keeps things from getting as messy as quickly. (Think of the list of statutes as a blog, and the codified version as a wiki.)

Returning to our main story, we’ve seen that Oregon has at least a plausible argument under contemporary copyright doctrine that it should be able to make Justia cut it out. If that answer is more ambiguous than we might like from an access to law perspective, it may be because copyright theory is also ambiguous on this score. Let’s look at the usual kinds of policies that people in law talk about when they talk about whether we should or shouldn’t give copyright in certain kinds of works.

There are three standard patterns for arguments against particular copyrights. If we plug “laws” into those patterns, we get:

The problem is that each of these standard moves comes with a standard counter-move. Arguments that are internal to copyright’s Bizzaro-world logic have a weird way of wimping out when they’re asked to challenge other copyright policies. Let’s take them up in turn.

The standard argument here is that copyright protects the originality of the human mind. It protects things that express the author’s unique personality. Here’s a famous passage from Justice Holmes’s Supreme Court opinion in Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co.:

The copy is the personal reaction of an individual upon nature. Personality always contains something unique. It expresses its singularity even in handwriting, and a very modest grade of art has in it something irreducible which is one man’s alone.

Under this theory, the government isn’t a person. It has no personality. The author of the laws is the populace as a whole acting through the legislature. Therefore, no copyright.

That rationale is attractive, and authorship arguments have a lot of force, particularly in European copyright doctrine. But they tend not to carry very much water in the U.S. today. There’re lots of cases extending copyright to collectively drafted junk. Think of corporate annual reports, produced by committee, which have absolutely zero personality. Not that very many people would want to make more copies of these snooze-fests (or that their corporate authors would object), but there’s not much doubt that they are copyrightable.

On the other hand, some governmental work is filled with personality. Justice Holmes’s pithy paragraphs have a lot more going for them than most corporate reports do. The authorship argument would concede that Holmes wrote his opinion as an agent of the government, but it’d still end up being swayed by his stately turns of phrase. Even when it comes to model codes drafted by private bodies, sometimes you can find an individual’s fingerprints all over the resulting document. Authorship theory might say that the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act is called “McCain-Feingold” for a reason, and that John McCain and Russ Feingold should share the copyright in it

Thus, the authorship argument proves too much and too little. Personality is neither necessary nor sufficient for copyright. Even if we took authorship arguments seriously, many governmental works, including all sorts of stuff that constitutes “the law,” could potentially surmount whatever hurdles it set up to copyrightability.

The main theory of copyright in the U.S. today is based on incentives. I’m sure you’ve heard arguments of this sort before. Copyright is the solution to a public goods problem. We give out exclusive rights against copying, so that creators can make money selling access to their works. That gives them a financial incentive to produce creative works that they wouldn’t produce otherwise. Exclusive rights are a tool for creators to recover the fixed costs involved in making the first copy.

On this theory, government doesn’t need to find another solution to the public goods problem of how to pay for drafting and enforcing the laws, because government is itself the solution to that public goods problem. You don’t need exclusive rights to make legislators write the law; you just vote the bums out if they don’t. You don’t need to give judges copyright in their opinions; writing opinions is part of the job description.

All of this is true, as far as it goes. But it doesn’t quite go far enough. The tricky part is that, as we’ve seen, most of the genuinely controversial copyright claims in legal materials involve claims over ancillary materials, not over the laws themselves. Think of John West’s page numbering and Key Number system. These are things that the government isn’t producing itself. Indeed, governments in 1880 probably couldn’t have produced West’s Key Number system. These annotations, like treatises and other material, make the law more explicable on a semantic level. They’re public goods. They’re useful. They’re privately written. And thus there’s a perfectly good incentives-based argument that copyright is a perfectly good tool to encourage their production.

From this perspective, it’s irrelevant that Oregon’s headers, numbers, and annotations were produced by government. There are other states in which the legislature just passes the stuff and the West publishing company adds all the annotations. If they’re copyrightable in private hands, why not in Oregon’s hands?

There’s another move that access advocates could make. Whether or not these things are actually drafted by government, perhaps they’re the sorts of things that should be drafted by government. That argument has less force than it used to. As a society, we’ve pretty much conceded that public-private partnerships are legitmate. We have privately-run prisons, privately-run highways, and privately-run charter schools. There’s no guaranteed knock-down argument against having private entities participate in drafting laws. Take the construction industry groups that write the building codes. These are private entities doing something to help the government out, and it’s a good thing, too. We have much better and safer buildings than we would if each city and county had to write its building code from scratch.

But once you’ve got private parties in the picture, there’s also no guaranteed knock-down argument that government should pay the private party in coin, rather than with exclusive rights. We pay the people who build and maintain private highways by letting them charge tolls; why not pay the people who draft laws by letting them charge for copies? Indeed, you could even do a tax-policy analysis and argue that copyrights are fairer and more efficient than paying for the drafting with higher taxes. That way, instead of the public at large paying for the drafting costs, it’s the people who actually use the results the most: the lawyers.

This is a hard theoretical problem. I don’t think that exclusive rights in the law are the right way to go, not at all. I’m just saying that incentive theory doesn’t provide the clear answer against legal copyrightability one might like or expect. (This happens a lot with incentive arguments in copyright; something that at first seems like it ought to yield a clear answer ends up spinning off all sorts of imponderable hypotheticals and empirical questions.)

What about the arguments I gave at the start of the essay, all the reasons why access to the law is vitally important? Well, the response to them is the oldest trick in the copyright book. Public access is important, you say? Well, the point of handing out copyrights is to increase access.

If we’re trying to increase the supply of good works available to the public, goes the response, we should look for works that aren’t being produced because potential authors don’t have the incentive to produce them. Give them a copyright in their creations, and they’ll actually start creating. Yes, the exclusive right means they’ll cut off access to some people under some conditions (i.e. not paying). But they’re still limiting access to works that wouldn’t exist in the first place if there were no exclusive rights. The public is a net winner. It’s a boomerang of an argument. The greater the need for access, the greater the need for copyright!

That’s the argument you see used for music; there’s not an immediately obvious reason to say why it doesn’t work for the law. This is the argument that Henry Wheaton made; it’s the argument that Oregon makes; it’s the argument that everyone in our rogue’s gallery of legal copyright claimants makes. They say, “It’s not easy doing the work we do. We need to recover our costs, or we couldn’t do it at all.” The Office of Legislative Counsel will charge you $390 for a complete 21-volume set of the Oregon Revised Statutes. That $390 goes to pay for the paper, for the costs of setting up the printing presses, and for the costs of compiling the laws into 21 convenient volumes. If you asked them, they’d say, “We’re making Oregon’s laws more accessible overall.” They’d say that if there were no Office of Legislative Counsel, Oregon’s laws would be in more of a shambles, not less, so they’re entitled to keep Justia from undercutting them on the price.

Historically speaking, they’re not completely wrong. There’s a plausible argument that Henry Wheaton’s high-quality reporters were sustained by his copyright and that West’s reporters are good because their headnotes and Key Numbers can be copyrighted. To refute these arguments, we’d need to go out and measure sales and costs and markets and look at things very carefully. Just like authorship and incentives, access fails to provide the unambiguous unanswerable theoretical argument that one might hope for by going to copyright theory. Access to the law is a hard, hard problem.

Or, perhaps I should say, it was a hard problem. There’s a huge difference between the problem with previously available technology and the problem as it stands going forward. The Internet changes the game. We get trivial transmission costs to send out documents to other people. We get perfect reproduction without corruption. We get search technologies that massively reduce the logistical burden of providing comprehensive indices. Put these together, and we can get, almost as a byproduct of producing the first copy of a work for any purpose at all, copies shared all across the world at low cost and with ever-increasingly reliability. If a court uses word processing to write its opinions because the judges find it easier to draft them that way, it now has everything it needs to make digital copies for the world. And once it releases a single digital copy to the public, we’ve all got it. All of us.

And that’s not the half of it. There’s another fundamental, perhaps even more overwhelming change here. Giving people computers and networking catalyzes large-scale distributed collaboration. A network of volunteers can now do things that previously only very large entities could have tackled. Open source software and Wikipedia are classic examples of this. I’d also point out that in this environment, you only need one or a few altruistic entities to be putting things online to do the work for everyone. Once the resource exists in digital form, posting it online pretty much solves the problem. Internet distribution is something that we know how to do and we know to do well. Free web server software, running on off-the-rack boxes, using standard software formats. We know how to do this.

Similarly, we’ve got all the building blocks we need to solve the citation and organizational problems. We know how to design good universal citation formats (e.g. by consecutively numbering opinions as a court produces them). All we really need are unique identifiers and some reasonable sorting system–and everything has a name and a location. There are many institutions that have the capacity to make the law available in the ordinary course of their business or out of the sense that the public good demands it. So perhaps the real heirs to Henry Wheaton’s legacy–his good legacy of high-quality reporting, rather than his unfortunate legacy of aggressive copyright claims–are the many institutions that are striving to do two things:

| Second, services like PreCYdent, AltLaw, and [v | lex](http://www.vmagazine.com/) are providing advanced tools to search and analyze those basic documents. They’re building better search engines for law; they’re building ways to cross reference things together. They’re creating, in other words, a value-added layer on top of this public-domain foundation, to make the law easier to find and easier to understand. |

The frontier of the possible is being pushed rapidly outwards. We can now get commodity publishing of the essentials for far less, proportionately speaking, than ever before. The place to compete is no longer on optimizing workflows to avoid introducing typesetting mistakes, as it was in the 19th century. The new goal for active competition is to take these basic primary documents and make them broadly usable to lawyers and the public.

This shift raises important questions. How should we ensure reliable access to primary legal materials? How should we encourage competition in providing innovative analyses of them? Where does copyright fit into this equation, if at all? What, in short, should we demand from the law when it comes to access to the law?

In setting out principles for thinking about copyright in this new age of technological access to the law, I’m not going to focus here on existing copyright doctrine. Rather I’d like to look at what the essential freedoms are in relationship to law. These freedoms are the ones that everyone ideally needs to have to consult and make use of “the law”; my argument is that computer and Internet technologies enable us to go much further in ensuring them than ever before. Think of them as guiding principles.

Once we have these principles in mind, there are a multiplicity of ways to integrate them back into copyright doctrine. They have various advantages and disdvantages; some of them would be cleaner to implement than others. There’s a fair amount of legal scholarship on these issues, some of it quite excellent. Lyman Ray Patterson and Craig Joyce’s 1989 article in the UCLA Law Review, Monopolizing the Law: The Scope of Copyright Protection for Law Reports and Statutory Compilations (36 UCLA L. Rev. 719, for you lawyers), is a good place to start. Here are some of the available routes to reform:

Some combination of some of these approaches will be necessary. It may seem strange for a lawyer to be arguing that the specifics of the law don’t matter so much as the underlying goals. But copyright has always looked to purposes when precedents are ambiguous. They are here, so it’s entirely appropriate to look to our societal goals to help us deal with those ambiguities. And, of course, for legal reforms (such as expanding Section 105), the whole point is that Congress can change the law to make things better.

The right to access: First and most fundamentally, people need to be able to get at the law. This puts a basic initial duty on the government not merely to publish the law but to publish it online in accessible formats with the right metadata, so that people can find it and know what it is. We shouldn’t exclusively rely on the government, any more than we relied on it exclusively in the 19th century. But governmental online publication is the first step, the one that makes the rest possible.

The right to distribute: Once primary legal information is online, anyone should be able to pick it up and republish it as they see fit. That could be coordinated with other materials in larger collections, it could be pushed out to mobile devices, it could be reformatted or sliced and diced in some clever new way. Law shouldn’t get in the way of people who are taking it on themselves to publish it.

The right to extract: Then there’s the intermingling problem. Anyone has to be free to do what Richard Peters did: to extract the public-domain legal materials and reproduce them. This is a strong principle, and needs to override any voluntary agreements to the contrary. That is, a private publisher shouldn’t be able to require that you give this right up if you get the legal materials under digital rights media management with a clickwrap contract. It shouldn’t matter that you click “I agree not to tell people what the law is.” You should still be free to tell people what the law is.

The right not to extract: The flip-side of this principle is important, too. You shouldn’t be able to make things hard to extract. No one should have to write a parser to strip out that green sentence from the midst of all the red that surrounds it. To the extent that copyrighted material has been so intermingled with public-domain legal material as to make it a significant challenge or to require significant work to extract the underlying material, there should be a right to redistribute the collection as a whole. Whatever the most accessible version of the law is, you have a right to use that version. One might object that this rule erases the incentive to make annotations. On the contrary, it provides an incentive to make your annotations cleanly, with a clear layer separation between the primary materials that are the law and the secondary annotations that help people understand the law.

The right to cite: Finally, there’s citation. Anyone, of course, is free to use the citations themselves; Oregon basically concedes this one. But to the extent that a citation system becomes a standard (and especially where government requires you to use a particular citation system), anyone should be able to reproduce the necessary citation information as part of their own materials. (West has sued companies that want to reproduce what’s called “star pagination”; that is, little flags in the text or the opinion that show you whenever the West case number changes. They’ve won in one federal appeals court and lost in another.) Otherwise, a standard citation system allows its creator to assert de facto copyright control over the underlying legal materials.

These principles aren’t unique to legal materials. They’re not new, either. Access, arrangement, and distribution have always been important. It’s just that when we look at legal materials, the case for these principles has become overwhelming. The Internet makes it possible for us to say that while previously we might have been willing to compromise and grant related copyrights in order to get legal materials before the public at all, now we can demand nothing less than full and unfettered access.

In early May, Justia said that it had no intention of accepting Oregon’s copyright claims and prepared a declaratory judgment action asking a federal court to declare that Oregon’s copyright claims were invalid. Oregon’s Legislative Counsel Committee, which oversees the copyright policy (unchanged since 1953), announced its intention to hold a hearing and invited Justia to testify on June 19, 2008. And then, in the words of Public.Resource.Org’s Carl Malamud:

There was a comprehensive briefing packet prepared for the committee, the members asked lots of intelligent questions, and then Dexter Johnson the Legislative Counsel recommended to the committee that they waive assertion of copyright on their statutes. The Majority Leader placed the motion, the President of the Senate called the vote, and the vote was unanimous. This was democracy in action and was great to watch.

June 19, 2008

Revision history:

This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States License. It is canonically available at http://james.grimmelmann.net/essays/CopyrightTechnologyAccess. It bears my name, but many people contributed:

I welcome your comments, critiques, and corrections.